Being a first-generation middle-class poet isn’t easy. I sit at a desk and peck at a laptop all day. Not poems; emails to colleagues, research summaries, proposed company policies. The Florida sun bakes the streets outside and I think back to the rural Midwest, the place I was apparently born, but don’t remember. I struggle to reconcile my surroundings with those of my small-town, blue-collar forebears, measuring myself against them on the yardstick of life.

Like all good, middle-class poets, my yardstick is a metaphor. Unlike them, my yardstick is also a yardstick. The words “United Auto Workers, Howard County, CAP Council” are pressed in solidarity and ink along its length between the 11th and 25th inch marks. The ruler’s an heirloom, once belonging to my grandmother, maybe my aunt or uncle, or possibly a cousin. All of them worked in Kokomo, Indiana factories. When I feel conflicted about being a degreed and urbane capitalist cog, I slide the yardstick out of the closet and look at it, and feel a little bit closer to believing that, yeah, I’m still kinda workin’ class.

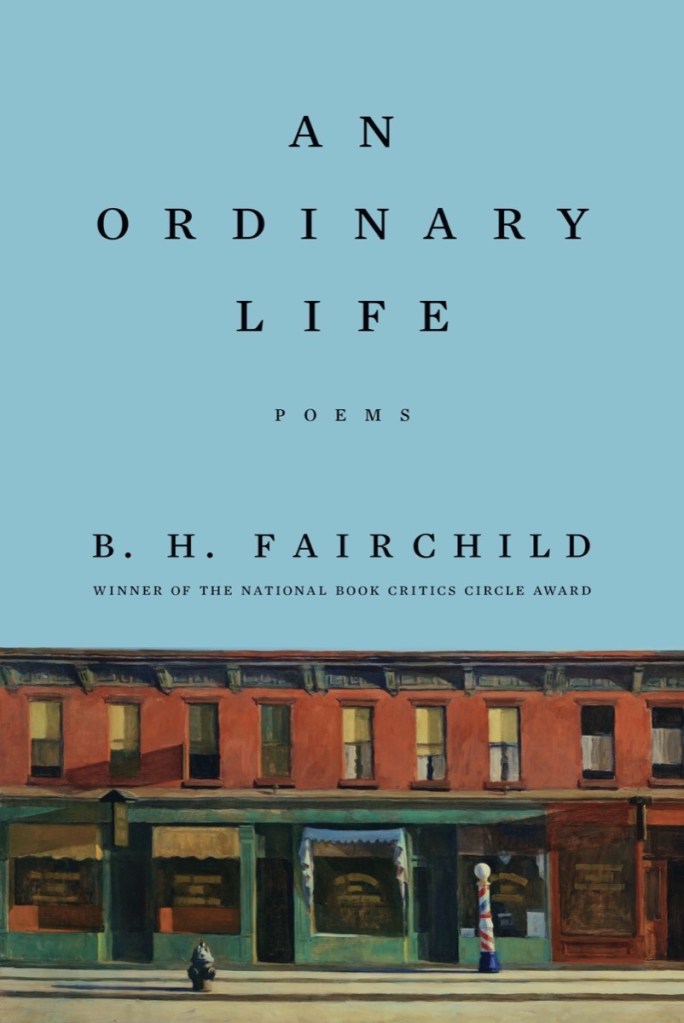

B. H. Fairchild’s latest book, An Ordinary Life (W.W. Norton, 2023), expounds upon a metaphor from his seminal collection, The Art of the Lathe (Alice James Books, 1998). A lathe is a machine that creates symmetrical objects by rotating wood or metal around an axis. The material is trimmed and formed by the machinist operating the lathe as it spins. “Lathework,” the poet once said, “holds the model for everything I have written, especially poems.” The craft of poetry–the requisite attention to detail, to “small matters” performed on the page–is like lathework. The lathe is Fairchild’s yardstick, a symbol of his father’s livelihood, against which he measures his own life and work as a poet.

When Fairchild ponders “The Hat” left on a bench, its “circularity without purpose”, that is until it rains and becomes a vessel, a container, he’s abstractly weighing the importance of poetry with more practical things. His hat is now magically “utilitarian and yet transcendent”. He really wants poetry to be, like the hat, a thing that is both beautiful and useful to society, specifically to his blue collar “origins that we felt were in the past but are in fact always revealing themselves in the future become present.” This utility is personified in “Poem Beginning With a Rejected Line by W.H. Auden.” Caroline Henderson, a school teacher living on the Great Plains in pioneer times, “loved the land in ways today we cannot / understand.” Henderson reads revolutionary philosophy and poetry, while protecting her daughter, Eleanor, from Dust Bowl storms by draping a wet cloth over her crib. Henderson prays “in her angry, solitary way” that she’d grow up and move away to study medicine one day. And that Eleanor does, returning at the end of the poem to pronounce her mother’s cause of death.

One aspect of An Ordinary Life I found intriguing, and in alignment with the focus on working class roots, is its dubiously presented and also weirdly specific allusions to left-wing politics coupled with subtle critiques of the consumerist/capitalist/imperialist tenor of ordinary American life past and present. Communist poets Paul Éluard and Meridel Le Sueur are named-dropped, as well as the Soviet poet Osip Mandelstam and the erstwhile People’s College in Fort Scott, Kansas. We hear about the irresponsible use of natural resources, the Spencerian survival-of-the-fittest mentality of American settler-colonialism, and its workaday descendant, the dog-eat-dog world. Fairchild’s alien caricature of the world of corporate leadership in “The Meeting of the Board” is the most subdued yet unflattering critique. Like Fairchild, the board members’ fathers “weigh heavily upon their backs”, but unlike Fairchild, who does his best to bring his father’s influence, good and bad, into the light, their “acquired grace of mercantile demeanor renders the daddies scarcely noticeable.” The atmosphere of the meeting is eerily calm, permeated by “the low rumbling of the voices of commerce” making decisions in their narrow self-interests. Their power seems ethereal, neither beautiful, nor practical.

The collection begins with more physicality. In “Welder,” Fairchild uses his father’s voice to frame working-class distaste for “his poet’s life” with delicacy, while reenacting for us the genesis of lathework (or more generally, metalwork, like welding) as a model for writing poetry. Fairchild is able to imagine the space his father is making, giving his son a place in his world where “It’s not poetry. But it’s what I do.” Fairchild can believe that that world hasn’t rejected him in the same way he rejected it by going off to college to study poetry. He sees a chance yet to reclaim his blue collar roots, including the “box of tools kept oiled / and free from rust, my steel-toed boots and fine / bronze cutting torch, a welding unit good / as new, and a pickup truck with a bed / where he can sleep, dream, ease the pains of work / and rise again to make a life.”

The reconciliation he wants with his roots goes back even further than Kansas and his father, as evidenced in the ekphrastic “The Watchmaker in the Rue Dauphine.” An early 20th Century photograph of a French watchmaker, busy at his craft, surrounded by the small but important things that go into his creations, is an archetype of the machine shop. The watchmaker represents a tradition of solitary artisanship, seemingly isolated from the machine shop in Kansas, but Fairchild can still say of them both, “This is the world. All there is of it.” The watchmaker’s shop and the machine shop exist in unworried ignorance of each other, but in Fairchild’s measure they are the same kind of place: a site of work, of artisanship, for the creation of things both beautiful and useful.

And so I slip my actual yardstick back into the closet and close the door. Another day, perhaps, I will need it. Until then I’ll have An Ordinary Life on the shelf in my office, a reminder of the need for solidarity. For now the book’s as crisp and clean as the administrative policy proposal I’m drafting for the review of my company’s board of directors, an exemplar of craft and a thing of beauty, and even practicality, if the board will care to see it.

Brian A. Salmons lives in Orlando and writes essays, poems, and plays, which can be found in Qu, The Ekphrastic Review, Autofocus Lit, Stereo Stories, Memoir Mixtapes, Arkansas International, and other places.

Find him on IG @teacup_should_be and Twitter @brianasalmons.

Leave a comment