with Dmetri Kakmi

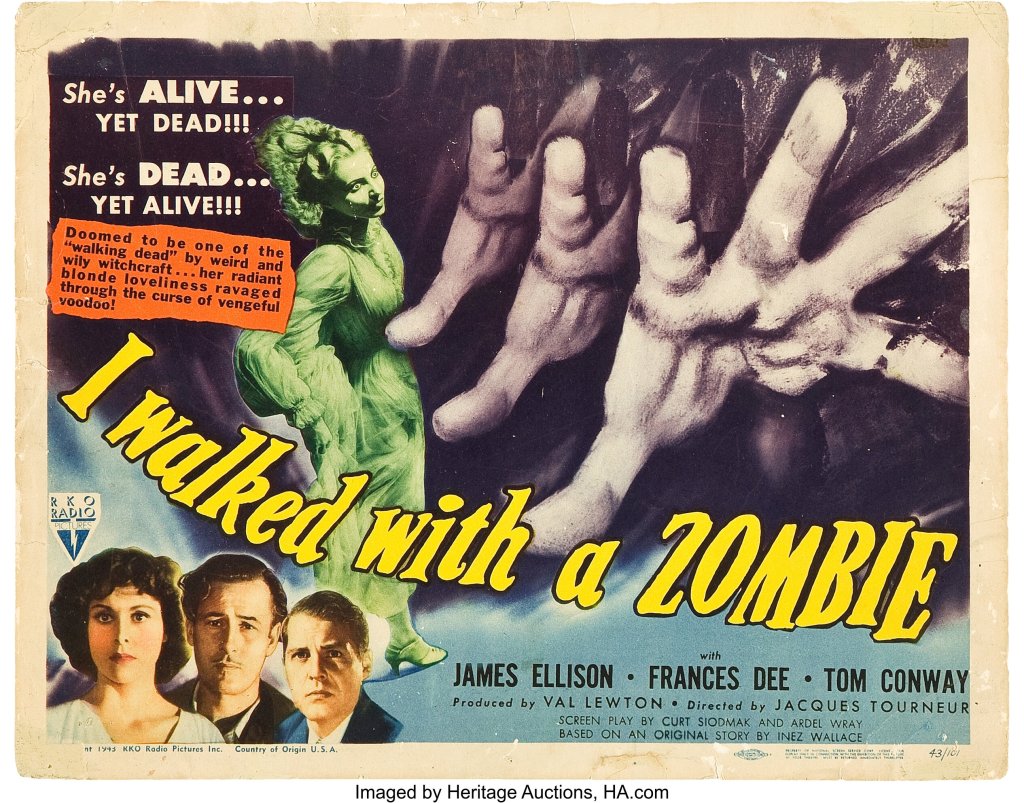

I Walked with a Zombie

USA, 1943

Director: Jacques Tourneur

Cast: Frances Dee, Tom Conway, James Ellison, Edith Barrett, Darby Jones

In an alternate universe I Walked with a Zombie would be called Jane Eyre and Zombies. There would be a couple of lame jokes, the feisty heroine would kick some undead arse while a hapless male hid behind the chaise longue, and that would be the end of a one-joke CGI spectacle. Fortunately, that was not the case here.

The redoubtable dynamic duo of of 1940s horror movies, Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur, aimed much higher. Despite the sensational title, I Walked with a Zombie is not scary. It is a masterpiece of subtlety and understatement. Made on a shoe-string budget in under a month, it ranks among the most beautiful horror movies made.

I suspect the best way to describe I Walked with a Zombie is to say it is eerie and weird, with more than a touch of poetry — a poetry of shadows. If tenebrosity could speak it would talk the language of Lewton and Tourneur’s film — a languorous, hypnotic interplay of light and dark and consonant with vowel that, like the magical incantation of the title, draws the viewer into a dreamworld where beauty is a mask for death and destruction.

Foremost, I Walked with a Zombie is a tragic love story. Thwarted passion and a desire to control is at the centre of everything that happens on Saint Sebastian, a post-slavery Caribbean island, that is anything but a tropical paradise.

‘Everything seems beautiful because you don’t understand,’ says Tom Conway’s Paul Holland in a mellifluous voice (he was George Sanders’ brother; honeyed voices must run in the family). ‘Those flying fish, they’re not leaping for joy; they’re jumping in terror. Bigger fish want to eat them. That luminous water, it takes its gleam from millions of tiny dead bodies. The glitter of putrescence. There’s no beauty here. Only death and decay.’

Cheery fellow, isn’t he? That’s why Frances Dee’s nurse Betsy Connell can’t help but fall for him, despite the fact that he is married and she is employed to look after his semi-comatose wife, Jessica Holland. But is Jessica suffering from a ‘tropical fever’, as the good doctor decrees, or is she dead and somehow able to peregrinate ethereally at dusk?

The question remains unanswered. Therein lies the film’s charm. We are not certain if Jessica truly lies with Baron Cimetière or if she suffers from acute melancholia after her husband stops her from running off with his half-brother, Wesley.

The depiction of human relations as complex, varied and riddled with ambiguity and contradiction should not come as a surprise. Pulling away from the kinds of horror movies Universal made in the 1930s, Lewton and Tourneur turned out smart films that draw on their respective cultured European backgrounds, but set in a contemporary American milieu.

‘Human, all too human,’ as that other chipper fellow, Nietzsche, wrote.

The same respect is accorded to black characters. Far from coming across like silly 1940s caricatures, everyone, from Theresa Harris’s Alma to Sir Lancelot’s calypso singer, is given a multilayered inner life and vital roles to play. This applies even to Darby Jones who plays the extraordinary figure of Carrefour (French for ‘intersection’). Monolithic, bug-eyed and eerily silent, he is the silence that surrounds the island’s historic slavery trade. He may even be a god that guards the gateway between life and death.

If I Walked with a Zombie is about anything, it is that appearances can be deceptive. ‘It’s beautiful here,’ exclaims nurse Betsy when she arrives on Saint Sebastian. ‘If you say so, Miss,’ says her black coachman. He knows better and, like the script itself, there is a world of meaning tucked inside the carefully chosen words and images.

Ambiguity is at the heart of all great horror stories. A level of uncertainty is essential for full effect. Is it really happening or is it a product of a disturbed mind? Are the events truly occurring or is there another way to see or interpret? That level of questioning opens doors of perception and interpretation, allowing even the most sceptical viewer to enter the story on a deeper level. Ultimately, that is the secret behind the success of Lewton and Tourneur’s most memorable outings, whether we are talking about Cat People (1942), The Seventh Victim (1943) or Curse of the Cat People (1944).

Dmetri Kakmi is the author of The Dictionary of a Gadfly (as The Sozzled Scribbler), The Door and Other Uncanny Tales, Mother Land, and When We Were Young (as editor). His gothic horror novel, The Woman in the Well, will be published in March 2025. He is currently working on a crime novel called The Perfect Room.

Leave a comment