with Dmetri Kakmi

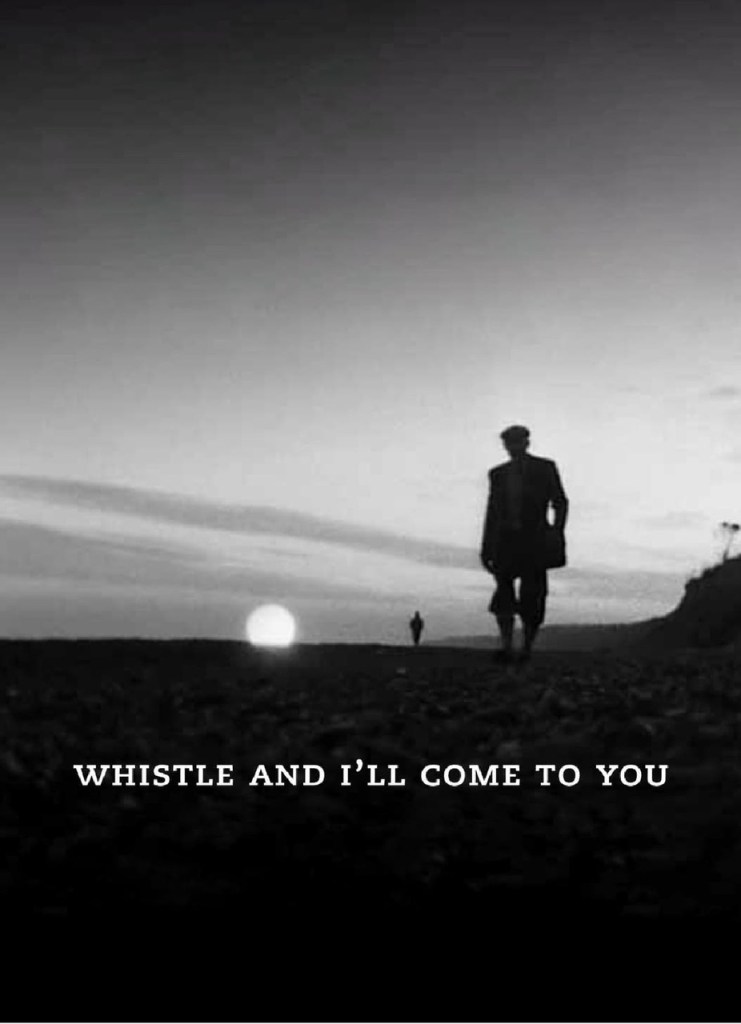

Whistle And I’ll Come To You

UK 1968

Director: Jonathan Miller

Cast: Michael Hordern, Ambrose Coghill, Freda Dowie, Weird Spectral Apparition

Cinema is the medium of sight and sound. It’s what you see and what you hear that matters, and how the two are deployed on screen to convey the essence of story. The opposite is also true. In cinema, what you don’t see and what you don’t hear is as important. Sometimes, silence and darkness speak volumes, illuminate worlds. A hint, a suggestion, can be a playground. Whereas to lay everything out on the table, to make a splash, can kill imagination. Contrast The Haunting (1963) with The Haunting (1999) and you will see what I’m talking about.

So there it is. Cinema as the art of contradiction and conundrum. Oppositional forces at work to create a whole. There aren’t many directors who can pull it off. Most are inept. Very few know what they are doing, and when they put their abilities to use they turn the screen into an electrifying canvas. They treat film as exploratory art.

One such is this extraordinary 42-minute film directed by Jonathan Miller, for BBC television. The short story ‘Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’ was written in 1904 by famed ghost story writer M R James. James was a Cambridge University provost and antiquarian. His best work grew out of a passion for arcane knowledge, with grumpy spirits released from ancient vaults by the unwary.

In Miller’s rendition of the story, Parkin, a stuffy old professor who is rather too sure of himself, vacations in a coastal town. Preferring to be alone, he spends his days walking the desolate shore and exploring an ancient cemetery. While poking around, he unearths a bone whistle caked in mud. ‘Finders keepers,’ quoth he, popping it in his satchel. He takes it with him and perceives, as he walks back to his hotel, that something appears to be following him along the beach. That night he cleans the whistle and finds a Latin inscription, which translates as ‘Who is this who is coming?’

He blows the whistle. Something comes.

What follows is an extraordinary ten or so minutes. The observational naturalism that comes from Miller’s years as a documentary filmmaker gives way to a series of expressionist black-and-white gestures and close ups of a man undergoing radical transformation from reasoned man to gibbering lunatic.

Throughout this delicious collage of jarring images we are not sure what is real and what is dream or fantasy. This radical abstraction of the senses has more to do experimental cinema than late 1960s commercial television. For the first twenty minutes, Miller’s direction is matter-of-fact, observational, which results in grounding the viewer in reality and then destabilizing them when order breaks down and the uncanny enters Parkin’s bedroom. The great Michael Hordern’s performance during these moments owes as much to silent cinema’s emphasis on facial expression and body language as it does to expert film blocking and disturbing use of sound. The end result is so effective, it’s hard to believe that much of what we see was improvised on set.

The other-worldly is elevated and made more unsettling because it is treated realistically, though with a great care of conception. A long shot of a specter silhouetted against a twilit beach is sublime and chilling. Another shot of what appears to be a twisting, coiling piece of black negative space chasing Hordern across the sand is alarming. ‘This is what great horror is about,’ I remember thinking on first viewing. Unnerving yet exultant, hinting at greater mysteries. Parkin’s nightmare of being pursued is a series of slow-motion convulsions, oscillating perspectives, moans, and contortions, as a fleshless form advances through space and time. We stare, holding our breath, not sure of what we see. At the end, we may take it either as real or delusion.

‘Who is this who is coming?’

It is the unraveling of a rational mind.

Dmetri Kakmi is the author of The Woman in the Well, The Door and Other Uncanny Tales, Mother Land, and When We Were Young (as editor). He is now working on a psychological crime novel called The Perfect Room. Though in light of recent real-life horrors he doesn’t see much point in writing.

Leave a comment