with Dmetri Kakmi

Kuroneko (Black Cat From the Grove)

Japan 1968

Director: Kaneto Shindo

Cast: Kichiemon Nakamura, Nobuko Otowa, Kiwako Taichi, Flying Cat Creature From Hell

You must have gathered I have a weakness for the ghost story. Nothing gets my blood racing like a frightful apparition floating eerily down a misty corridor. Hush, my beating heart! Joy is on the way.

As you would expect, there are plenty of frightful goings on in Kuroneko.

Released four years after Shindo’s highly successful Onibaba , the plot for Kuroneko concerns vengeful spirits of a peasant mother and her daughter-in-law who are raped and killed by samurai. As often happens with these things, the dead women make a pact with a passing cat demon that allows them to manifest as refined ladies who, in turn, murder samurai and drink their blood. All goes according to plan until Gintoki returns from war. Now a splendid samurai in his own right, he goes looking for his mother and wife only to find a burned down house and the women missing. To make matters worse, the governor of the district orders Gintoki to destroy the ghosts that are killing samurai. Of course, the minute the lad lays eyes on the spirits he knows who they are. Here is the dilemma. Will he destroy his mother and wife? Or is he going to do everything he can to keep them near?

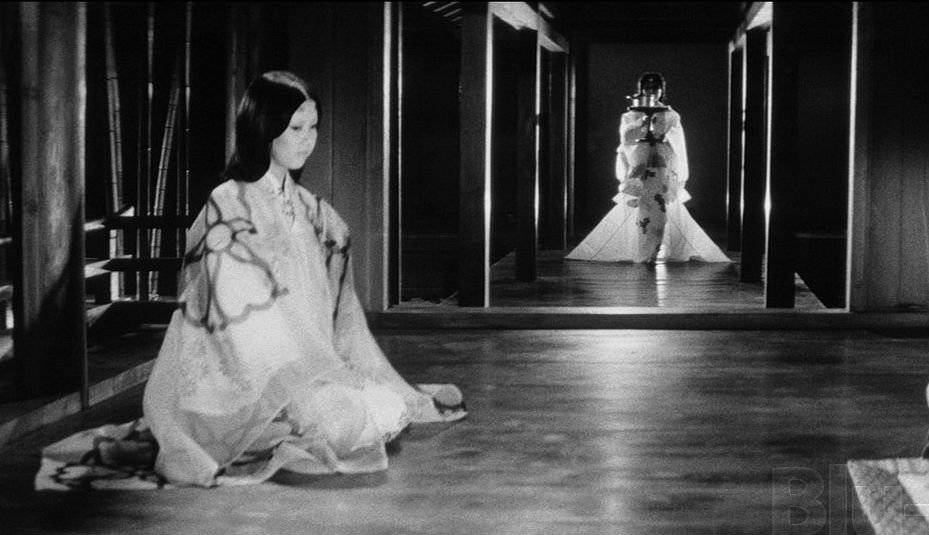

It’s a poetic, atmospheric tale that is the equal of Onibaba, if not in brutality then in eroticism and lyric beauty. Rarely has a filmmaker gone to the trouble of creating such visually stunning images that enhance the otherworldly aspects of the plot and transport the viewer into an unsettling nether realm that is bewitching as it is dangerous.

If forced to choose one word to describe this exquisite film I’d opt for “seductive”. Shindo engages in an act of active seduction through beguiling imagery in the way a writer might use words to seduce a reader, drawing them in so far into his sensibility that escape is neither possible nor desirable. You are ravished despite yourself.

The beautiful images correspond to the women at the centre of the drama. They draw us in and keep us there in the same way as the young ghostly woman draws the doomed samurai deep into the bamboo grove and the house that, appropriately enough, exists and doesn’t exist. The mansion is as much a phantom, a conundrum, as the women. It and they are there while not being there at all. They are an illusion that plays on the visual cortex and torments the mind with what-ifs. What if Gintoki had not gone to war? What if he hadn’t come back a famous samurai but just an ordinary farmer?

That sums up the allure of the ghost story. Past and present merge. Reality and fantasy are indistinguishable. There’s crossover and overlap. And in between the wafer-thin veil is a very human drama of injustice, class disparity, love and family loyalty.

One of my favourite sequence—and it’s hard to choose one in a film that contains so many—comes early in the film. It’s of the first samurai the women lure to his death. Drunk on power and glory, he’s a bloated, prideful sod who gets hat’s coming for him. As it turns out, he’s also among the scavengers that killed the women at the start. As they meekly attend to his needs and ply him with sake, the walls around him evaporate and the bamboo forest comes into the room. Or does the room go out into the forest? It’s hard to tell. Inside becomes outside and outside inside. The mansion appears to have no walls, but the bamboo grove itself. The billowing curtains hint at the ethereal nature of the world the samurai has unwittingly entered. The long corridor into which the mother-in-law vanishes seems to have no beginning and no end. And this is all done with cross-lighting and overhead spots taken from Kabuki and Noh theatre.

In the end there are no winner and no losers. “All are banished,” as Shakespeare wrote. Human folly leads to greater human folly. What seemed the right thing to do at one point turns out to be a very stupid thing to do later on. Better yet, there is no attempt to rationalise what we have seen. It is an oft-told tale of strange and weird things that remain strange and weird, and of a world where reality and fantasy mingle to form a new way of being and seeing.

Dmetri Kakmi is the author of The Woman in the Well, The Door and Other Uncanny Tales, Mother Land, and When We Were Young (as editor). His essays and short stories appear in anthologies. He is working on a psychological crime novel called The Perfect Room.

Leave a comment