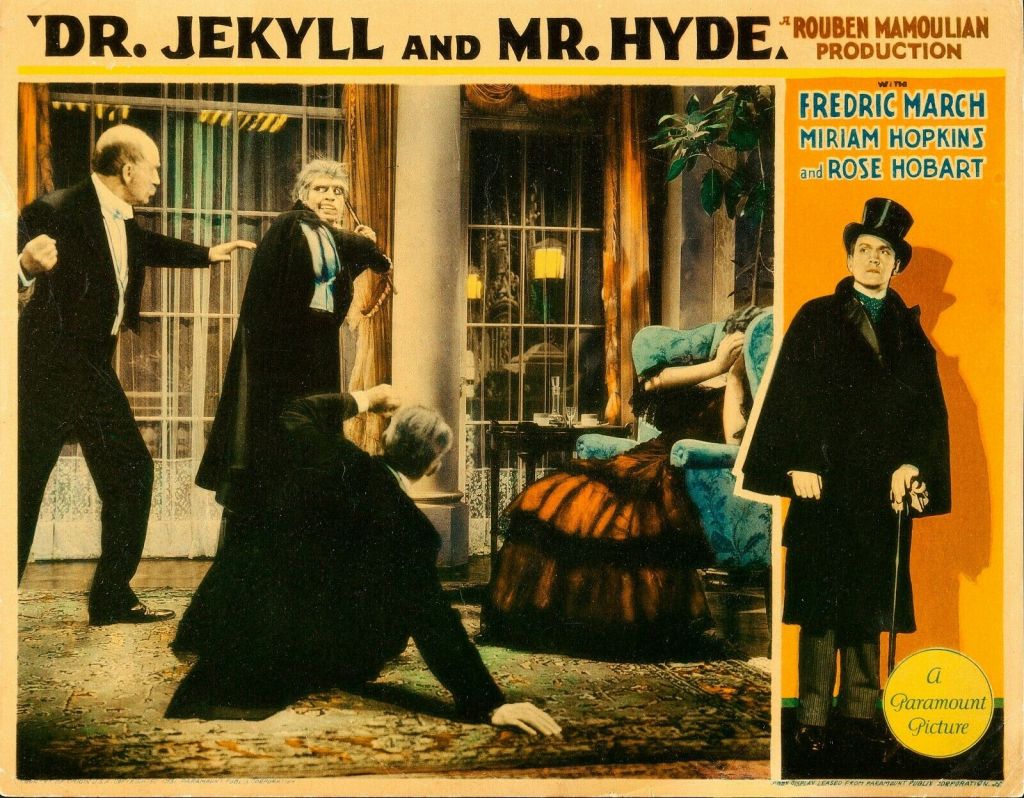

with your host, Dmetri Kakmi

Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

1931, USA

Director: Rouben Mamoulian

Cast: Frederick March, Miriam Hopkins, Rose Hobart, Edgar Norton

On a recent visit to Edinburgh, Scotland, I stayed in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Georgian terrace. It was grand, to say the least. From my room in the upper reaches of the house I could see over the higgledy-piggledy cobbled laneways and rooftops of the New Town towards the Firth of Forth. Stevenson did not write The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde there (that was in Bournemouth), but I was borne aloft by the thought that he and I occupied the same house, albeit in different time zones. A phantom cohabitation, if you like, brushing shoulders in corridors and stairwells.

I chose to stay there because the celebrated book is a favourite. A genuinely subversive take on the genre. If you are only familiar with the film adaptations, you are in for a surprise. Several surprises, actually.

First, the novella is not what you expect. Published in 1886, a year after homosexuality was criminalised in England, the book is redolent of the repressed and the unspoken in polite Victorian society. Second, unlike the films, it is not told through Dr Jekyll’s eyes. As was common for the early gothic tale, the novella is recounted via a series of newspaper articles, letters and reportage pieced together by Gabriel John Utterson, a London-based legal practitioner, who investigates the peculiar goings on at the Jekyll residence. Last, Mr Hyde is not a hideous brute, but a degenerate, somewhat malformed young man who inspires feelings of repugnance and fear. Daringly, Stevenson hints at Jekyll/Hyde’s homosexual trysts in a Soho bachelor pad.

Homosexuality played a larger role in the first draft, but Stevenson was advised to excise. What remains is tantalising insinuation. (I’m still waiting for the publication of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’s Big Gay Gang Bang.)

Read with the latter point in mind, the multifarious tale is, in part, about the disparity between public and private faces — what is present by day and what comes out at night. What must be hidden and what can be shown. Of course much of this pivots around sex.

Class hierarchies also play a part. Dr Jekyll is wealthy, handsome, debonair. Hyde is the opposite. The former is associated with upper-class breeding and innate goodness. Hyde is linked with the base working classes, the degenerate and the corrupt. Jekyll goes in the front door of his stylish address; Hyde goes out the back door into labyrinthine laneways. Long before Freud, Stevenson suggests the disparities between the two are superficial and quickly eliminated.

The book was a sensation, spawning many theatrical and film adaptations. Rouben Mamoulian’s lavish film version is by far the best. As one of the great cinematic experimenters, Armenian born Mamoulian deploys a sophisticated visual language that highlights themes and places the audience in Dr Jekyll’s head from the start. Far as I know, this is the first point-of-view camera in a horror movie history.

For the opening minutes we do not see Frederick March’s Dr Jekyll; we see what he sees, as he takes a carriage from home to lecture hall. It is only as March passes a mirror inside his home that we see what he looks like — a suave gentleman at the apex of London society. Similarly, the first time Jekyll (and we) behold Mr Hyde is when Mamoulian’s camera looks out of March’s eyes as he stares into a laboratory mirror to witness the birth of his slavering alter ego. The many lingering wipes and measured dissolves create thematic links while providing access to Jekyll’s state of mind.

Frederick March gives the performances of his career. His usually wooden, rather pompous screen persona is perfect for Jekyll. And he really lets loose as Hyde. Miriam Hopkins is outstanding as bar singer/prostitute, Ivy Pierson. Her swinging, pendulum-like leg, as she tells Jekyll to ‘Come back soon, won’t you?’ after he rescues her from a drunk is a formative image of horror cinema, linking sex with danger. It is an invitation she will regret.

Visual style is a slave to form and content. That is why the first time Jekyll drinks the potion, the camera placement makes it look as if he pours the liquid into the lens and therefore down the viewer’s throat. Mamoulian’s subjectivity is immersive. It pulls in the audience and brings out the story’s universal qualities. Extremes of behaviour, he is saying, are dormant in all. If it can happen to a civilised man like Jekyll, it can happen to you.

That is why Stevenson’s story touched a nerve; we can all relate to it. There is a porn version as well as a sex change in the 1970s. I cannot bring myself to see the musical.

At the most obvious, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is about man’s duality. The good, the bad, the light, the dark — and the force of will we exercise to balance the two. On a more amusing level, it is about a sexually frustrated man who goes on a bender and wakes up next morning thinking, ‘What the hell happened last night?’ The ending is cautionary and of its time. The cinematic pleasures are timeless.

Dmetri Kakmi is the author of The Dictionary of a Gadfly (as The Sozzled Scribbler), The Door and Other Uncanny Tales, Mother Land, and When We Were Young (as editor). His gothic novel The Woman in the Well will be published in 2025. He is currently working on a crime novel called The Perfect Room.

Leave a comment