with Dmetri Kakmi

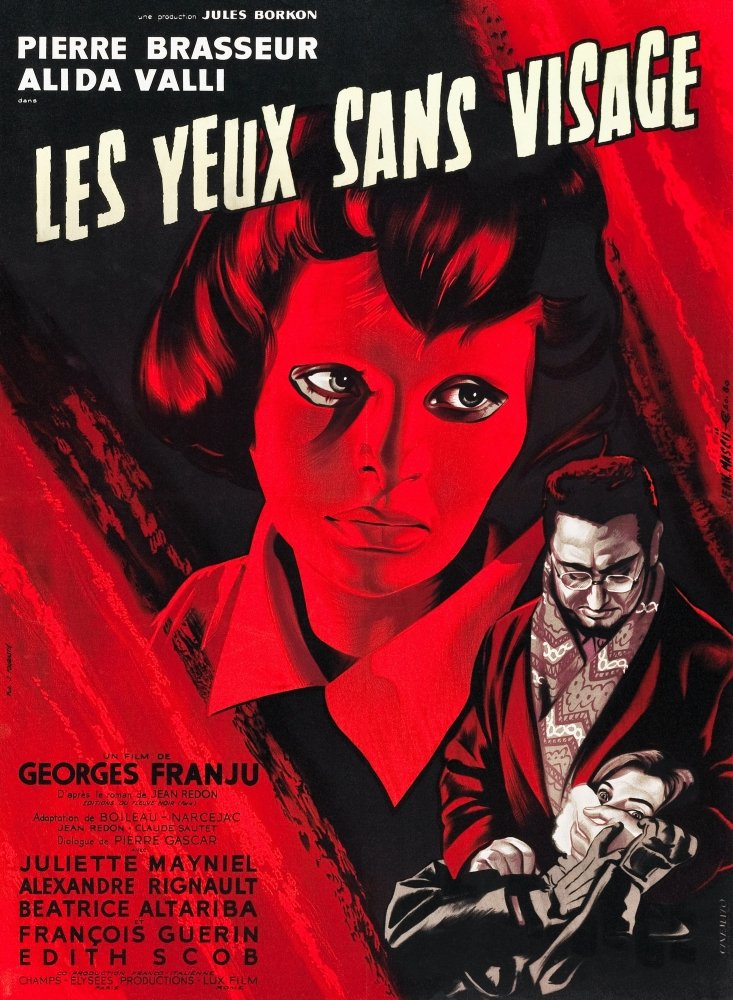

Les Yeux Sans Visage (Eyes Without a Face)

France, 1960

Director: Georges Franju

Cast: Pierre Brasseur, Alida Valli, Édith Scob

The final minutes of Les yeux sans visage are the most beautiful in the history of horror cinema. A plastic surgeon is determined to perform a face transplant on his daughter Christiane who was disfigured in a car accident, for which he was responsible. With the aid of a female assistant the surgeon kidnaps young women, removes their faces, and tries unsuccessfully to restore his daughter to her former glory. After many failed attempts, a guilt-ridden Christiane frees the final victim, kills the assistant, and releases the dogs and pigeons her father keeps for experiments. The dogs maul the father. Surrounded by pigeons, Christiane wanders into the night, a plaintive phantom with its face covered by a mask.

It’s an unsettling yet beguiling sequence. Rewatching it, I am reminded why I love horror movies so much. Amid the viscera there are moments of startling beauty and clarity—moments that are awe-inspiring and transcendent. It’s easy to say that horror is about fear of death. Harder to acknowledge that it also offers a peek behind the curtain that separates the known from the unknown, a universe of beauty, chaos and terror that lies beyond limited sensory experience. In short, horror movies open a window on the numinous, with all its mystery and other-worldly allure.

French cinema is largely the cinema of abstraction and philosophy; it slide from realism to the conceptual and phantasmal with such ease that it can be disorienting. Jean Cocteau is perhaps the greatest exponent of this kind of cinema. Much as I appreciate his work, however, I prefer Franju. He is cinema’s great poet because his is a more delicate sensibility. There is something almost unreal and evanescent about even his most realistic films and he possesses a wistfulness that touches a deep core. Coming out of the short film La premiere nuit (1958), for instance, is like emerging from a dream you want to plunge straight back into.

Reviled on release, Les yeux sans visage is now considered a classic. It contains such shimmering images that they’re almost distracting; you don’t want to read the subtitles in case you miss the visuals. Every shot brings out the tragedy and the terrible poetry of the gruesome subject matter, making it an anxiety provoking experience that is not easily forgotten.

Édith Scob was Franju’s muse. He brought out the best in her and she in him, which is why her Christiane is among the great female monsters. Both terrifying and bewitching, she stands proudly beside Elsa Lanchester in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935).

Scob appears in many Franju films and she is especially memorable in Judex (1963), where her child-like tremulousness is put to great use in yet another oneiric fable. Although we do not really see Christiane’s face in Les yeux sans visage, Scob’s expressive orbs peer forlornly through the eye holes, bringing life to the mask’s inexpressive Noh-like planes. She is conversely a fairy tale princess, fashion model and a horror-movie monster, wandering out of the wilderness to roam among uncomprehending humans.

Masks hide as much as they reveal, hinting at what may lie beneath. They are a lie and a secret you want to expose. They may also be an inner reality brought to the surface. A mask in ancient Greek and Japanese theatre stands in for thoughts, feelings and human archetypes, as well as posing an enigma that may never be solved.

Donning a mask to hide her destroyed face, Christiane defies and transcends beauty standards. By doing so she moves into another realm of being. She is the reviled outsider—outside convention even as she attempts to reenter the world for the first time since her exclusion. Given the tone of the closing images it’s not clear if Christiane wants to rejoin civilisation or if she is now fastened to the dogs of chaos.

We do not find out what becomes of Christiane when she leaves her father’s house. But we know she went on to inspire many a horror movie character, especially Michael Myers in Halloween (1978) and any number of masked killers in slasher offerings. In an inspired homage, Leos Carax even has an older Édith Scob don a mask at the end of Holy Motors (2012). It appears Scob/Christiane is legend. So is Les yeux sans visage.

Dmetri Kakmi is the author of The Dictionary of a Gadfly (as The Sozzled Scribbler), The Door and Other Uncanny Tales, Mother Land, and When We Were Young (as editor). His novel, The Woman in the Well, will be published in April 2025. He is working on a crime novel called The Perfect Room.

Leave a comment