with Dmetri Kakmi

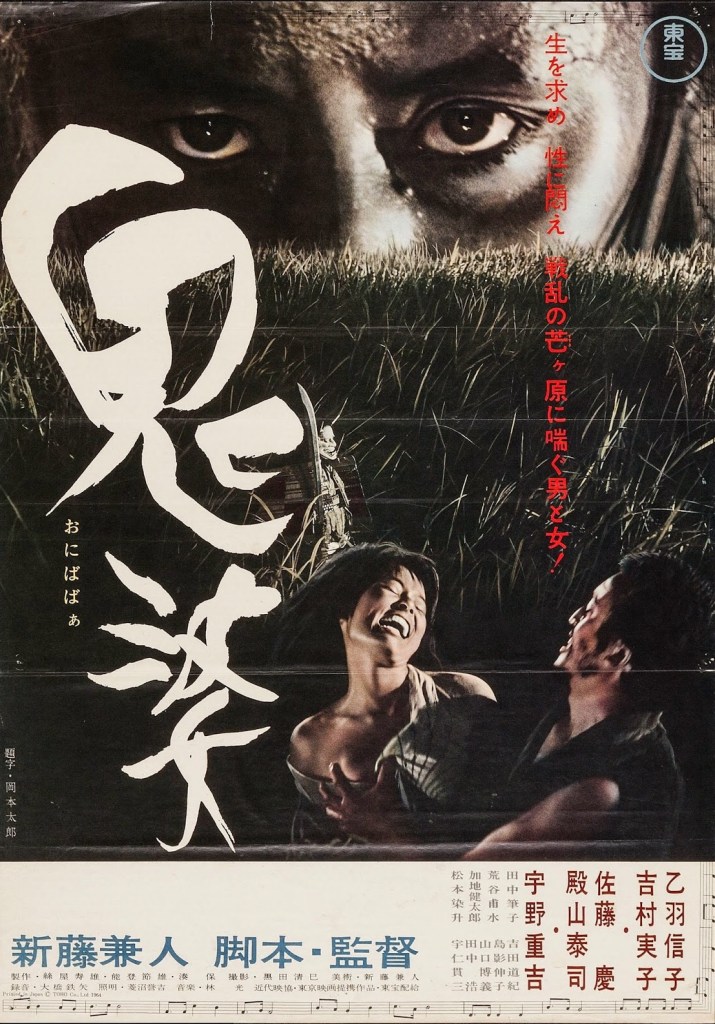

Onibaba

Japan 1964

Director: Kaneto Shindō

Cast: Nobuko Otowa, Jitsuko Yoshimura, Kei Sato, Taiji Tonoyama

A film begins the moment the credits appear on screen.

As we see with Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Scorsese’s Cape Fear (1991), the conception of the opening credits is important. You don’t talk; you don’t reach for popcorn. You don’t even breathe! You turn off your phone and pay attention because these vital minutes—the lettering, the music, the images or lack thereof—tell you more about what you are about to see than anything else. Within these carefully modulated minutes, a mood is set, a world and sensibility is established, and a theme suggested.

How do you the translate the opening credits of Onibaba into words?

You might begin with the moan of the wind in a field of waving susuki grass; you could mention the hissing of the reeds as they bend, and the gaping black hole, like a negative space, in the middle of a vegetative world; you could venture to note the circle of white light, floating like distant hope, as the camera peers from inside the pit up toward the sky; you will doubtless want to touch on the insinuation of the epigraph as it appears in Japanese kanji, white on white, almost unreadable, inside the burning circle.

The inscription is: The Hole, its darkness has lasted since ancient times.

Next the image returns to tossing reeds that give birth to the film’s title—鬼婆—(Demon Hag) and the remaining credits against a jagged, abrasive, discordant, musical score. It seems inappropriate, this music, more suited to a modern jazz club than 14th century Japan. Then you hear the primitive note of Taiko drumming, the shriek of a saxophone, and alarm sets in.

Already unsettled, you know you are in for an unforgettable experience. There is no escape from this field of wild reeds and the two women who live there, like debased animals, trapping and killing samurai so that they may strip the men of clothes and armour and make a living for themselves in a barbarous world.

Equally one might state that landscape is as vital a character in a story as the humans that occupy a drama. Setting, place, environment… Water, sky, and an undulating, restless sea of reeds. Combined they generate character and story. One cannot exist without the other. Landscape is the fountainhead from which all else springs. Without it there is nothing.

That is the case for the two women at the heart of this supernatural drama of the grotesque. From the opening moments Kaneto Shindō identifies them with the landscape in which they live, framing their interdependence against a density of reeds that blocks out the outside world, limits the horizon and at times even erases the sky. The women are dominated by riotous growth. Judging from their feral faces, it is hard to know if they’ve always been like this or if their circumstances made them thus.

Tellingly, the film is also known as The Hole, a more accurate title, in my view.

The story is inspired by a Shin Buddhist parable of the “bride scaring mask” where a cursed mask worn to scare a victim sticks to the skin and tears off flesh when removed. It also bears similarities to cautionary tales of elderly demon women who haunt lonely places and feast on human flesh.

Drawing on these Japanese traditions, Shindō paints a post-apocalyptic world of brutality and moral degeneracy where women in war are both victim and assailant, using sex to lure samurai and butchering them when the men are most vulnerable. (Ugetsu Monogatori also touches on this theme.)

In Onibaba sex is primitive drive. It governs every aspect of life. The bamboo is an abstraction that redefines cinematic space. It is a proxy for the women’s pubic hair, waving enticingly in the breeze to attract men to the sucking marshiness of female pudenda. The primordial hole in the field stands in for the hole between the women’s legs to which men are drawn and which eventually brings about their demise. Far from coming across as misogynistic, the grim faced and determined mother-in-law and daughter-in law team are portrayed as strong, cunning, resilient and hellbent on surviving a world riven by male greed and brutality.

It is only when another man appears and the young woman is drawn to him that camaraderie evaporates between the women and rivalry erupts. Competitiveness and resentment manifest as desperation and open hostility.

Scared of being abandoned, the mother-in-law dons a stolen demon mask to scare her daughter-in-law into staying, and then finds she can’t remove it. Terrified the older woman has turned into a demon, the young woman flees. The inevitable chase ends at the eponymous hole—the beginning and the end. Here we see a return to that opening shot of the camera looking out from inside the pit. The agile young woman leaps over it easily, as she has done before. As the older woman follows, she is weighted down by the knowledge that she is supplanted in nature’s pitiless sexual hierarchy. Paralysed by redundancy, she leaps into nullity and freezes mid-air.

Dmetri Kakmi is the author of The Woman in the Well, The Door and Other Uncanny Tales, Mother Land, and When We Were Young (as editor). He is currently working on a crime novel called The Perfect Room.

Leave a comment